Global trade networks connect countries by buying and selling goods and services. It is like a huge network that connects different parts of the world, helping them share what they make and what they need.

These networks are important because they help countries grow and allow people to enjoy products from all over the world.

So, what is the definition of a global trade network? What is its history and who are the key roles and challenges of this global trade network? Check out this explanation!

Understanding the Global Trade Network

Source: U.S Mission Geneva

What is the Global Trade Network?

According to StudySmarter, Global trade means buying and selling things across country borders. It’s also called “international trade” and happens when countries trade goods with each other.

This trade involves a series of steps where countries get raw materials, turn them into products, and then sell these products to other countries.

In this trade, if a country gets products from another country, those are called imports. When a country sells its products to others, those are called exports.

Why It’s Important

This global trade network makes sure that products like fruits, electronics, and clothes can be sold in places far from where they are made. It helps countries earn money and gives people more choices in what they can buy.

Countries that trade with other countries usually grow faster and become better at making things and coming up with new ideas. This happens because global trade makes countries start new types of businesses to meet the needs of other countries.

Trade between countries can also help build peace. It builds understanding, teamwork, and friendly relations between countries. This is because trade brings people together, and when they trade, they also share cultures and ideas.

Historical Evolution of Global Trade Network

Source: Adobe

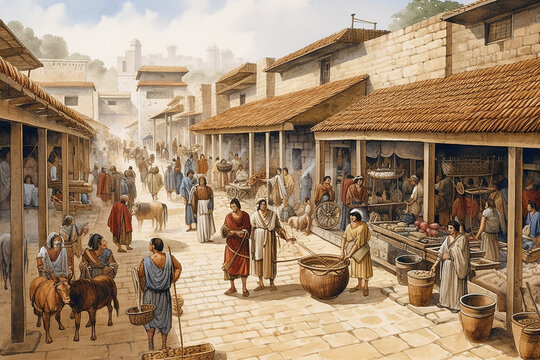

In the early Middle Ages, European trade, as in Roman times, used the Mediterranean Sea to move goods across the region. This sea connected Europe, Africa and Asia, encouraging the exchange of cultures and ideas since the 3rd millennium BC. This network, known as the “Mediterranean Sea Trade Complex,” played a large role in early global connections, more inclusive than the Silk Road.

By 1200, Europe began to shift from agriculture to more extensive trade, but faced challenges such as attacks from bandits. The Crusades brought back spices, silks, and perfumes, boosting European trade and causing the growth of cities, especially in Northern Italy and Northwest France.

The Hanseatic League, which focused on sea trade in the Baltic Sea and North Sea, organized trade fairs and helped foster new free and independent cities. This period marked a move to value individual talent over family background, leading to the growth of the middle class and the rise of Democratic Capitalism.

The Hanseatic League was a protective group in Europe, ensuring safe trade and creating laws for merchants. Trade fairs were large organized events where shops were easily identifiable by the goods they sold or their region, making it easier for buyers to do their shopping.

Key Players in Global Trade Network

The main players in global trade include countries, big companies, and organizations that set trade rules, like the World Trade Organization (WTO).

Countries decide what they want to buy and sell. Companies make and ship products. Organizations like the WTO help make sure trade is fair and solves problems when they happen.

The International Monetary Fund or IMF insights into global economic policies also provide a deeper understanding of the interactions between these entities and their impact on trade.

The Challenges of Global Trade Network

Source: Realtor.com

The global trade network helps countries buy and sell goods to each other, but it faces many challenges:

1. Trade Barriers

Things like taxes and limits on the amount of goods that can be traded make buying and selling goods between countries more difficult and expensive.

2. Shipping Challenges

Moving goods across countries can be complicated and expensive due to different rules and the need for good transportation.

3. Money Changes

The value of money can go up and down, which can change how much it costs when trading with other countries.

4. Unstable Situations

Issues such as fights between countries, economic problems, or sudden changes in regulations can complicate trade.

5. Culture

Not understanding or respecting other cultures can cause problems in trade.

6. Environment Concern

Trading a lot can harm the environment, such as causing more pollution from ships.

7. New Technology

While new technology can help trade, it also brings problems such as cyber attacks and the need to keep up with changes.

8. Protecting Ideas

It is difficult to keep ideas safe in different countries as some places do not protect them well.

9. Risks in the Supply Chain

If something goes wrong, such as a natural disaster or factory problem, it can stop production or delivery of goods.

10. Following the Rules

Each country has its own trade rules, and it can be difficult for companies to follow them all.

To solve this problem, countries need to work together, use new technologies wisely, and make fair rules that will benefit companies as well.

Hi-Fella as a Global Trade Network Platform

To address the challenges of the global trade network, you can use the hi-fella platform.

Hi-Fella is a digital platform that helps people and businesses connect to trade around the world where you can discover new opportunities and partner with others. Let’s join now!